By Lia Keener

When you Google “Oysters Berkeley,” the first thing that pops up is a long list of restaurants, ranging from Bag O’Crab to Great China and beyond, but there is no mention of the history of the oyster banks of the East Bay. These oyster banks are steeped in history rooted in the precolonial lives of Indigenous communities, and they are witnesses to the rise of what is now the modern day East Bay. Recent development projects and infrastructure have fundamentally altered the ecology of the oyster banks and have destroyed several traditional Ohlone shell mounds, formations composed of shell and soil formed by Indigenous groups once living along the coastal East Bay. Though many of the shellmounds have been destroyed, others remain buried beneath buildings and business to this day, quite literally making up the foundation of parts of the East Bay. Though these histories may seem hidden from view, they remain critically relevant to our understanding of the past and to our path forward as we navigate global climatic changes and radical shifts in East Bay ecology.

History is never neutral. It is full of injustices that reverberate through to the present day, and it is important to understand the past in order to better grapple with the challenges of the present. In the case of the Berkeley oyster banks, the cultural and ecological devastation brought by white settlers and the subsequent historical erasure of Native identities by white society at large has served to disconnect modern day residents with the reality of the lands they live on. Learning about the past allows us to more accurately place our own lived experiences in a historical context, and we become more able to appreciate the layers of time and change that have shaped the spaces we visit. Beyond offering context, history also offers solutions. From understanding the events of the past, we can learn what went wrong, who was wronged, and how to avoid doing wrong in the future, because, as the old adage goes: if you don’t know history, you’re doomed to repeat it.

East Bay Oysters lay at the cross-roads of both cultural and ecological destruction, both as a native species suffering from over-consumption by white settlers and as a structural building block of Ohlone shell mounds, many of which were destroyed by construction-minded East Bay developers. Analyzing oysters within the context of the modern day also reveals the disconnect between modern day consumers/residents of the East Bay with the reality of the ways we interact with the world around us.

Many might think, given that the East Bay is only a couple of miles from the ocean, that oysters eaten in East Bay restaurants are native to California and to the West Coast at large. However, this is far from the truth. Today, the oysters eaten in restaurants all along the West Coast are actually native to Japan. These Japanese oysters were brought to the United States in the 1920s in order to supplement the rapidly dwindling native Olympia oyster populations, which plummeted following their rise in popularity as a food item in San Francisco. Human appetites were not the only culprits for the demise of the Olympia oysters, as pollutants flowing into the Bay from nearby paper mills also took a serious toll on Olympia oyster beds.

Prior to European colonization, however, native Olympia oysters numbered in the millions, blanketing parts of the ocean floor in the East Bay and making up an integral component of the diets of many Indigenous communities living along the West Coast. Though the Ohlone Tribe is often cited as the prominent Indigenous group native to the Bay Area, the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe is actually the amalgamation of over forty distinct tribes and is a generalized term that was propagated over time by European settlers. Native oysters made up not just an important food source for local Indigenous tribes, but also as a structural component in the formation of shell mounds, constructions of deep cultural importance that left a lasting mark on the land.

These shell mounds, of which there were once over 400, served as burial sites, areas for trade, community, and ceremony, and those still intact are historical records of ecological conditions and cultural practices dating back thousands of years. Oyster shells, among other byproducts of life in the Bay Area, were used along with soil to bury the dead in the shell mounds, and, over time, these mounds grew to reach extraordinary heights, some over thirty feet tall. Following European settlers’ arrival, the genocide of Indigenous peoples living in the Bay Area, these shell mounds were often destroyed by land developers seeking to construct new buildings and further the growth of East Bay cities.

The destruction of these culturally and historically significant shell mounds overlapped almost perfectly with the plight of the native Olympia oysters, both being remnants of a very different California and both facing the threats posed by European settlers. While there is no way to recover the shell mounds that have already been destroyed, there is ongoing activism to prevent further construction on shell mound sites, such as the one in West Berkeley. Indigenous activists advocate against development on these sacred sites, seeking to preserve the history buried beneath layers of asphalt and cement.

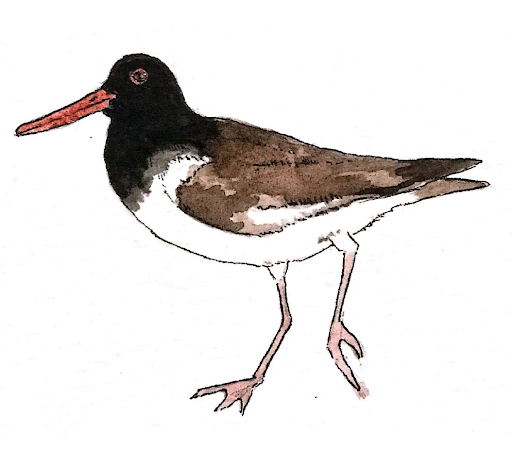

Preservation of Olympia oysters is also gaining momentum, with serious oyster restoration initiatives underway, and encouraging progress has already been made. In just one year, two million Olympia oysters have been reestablished in the waters of the San Francisco Bay, latching onto man-made reefs and boosting the ecology of the Bay Area. A cascade of positive effects has followed the oyster resurgence, because not only do these oyster reefs act as a buffer, limiting the intensity and lowering the impact of ocean waves by up to 30%, but they also serve as potential habitat space for countless other ocean dwelling species. The oysters themselves also play an important role in their food web. They support populations of oyster-feeding creatures like oystercatchers and also serve as ocean cleaners, removing harmful substances from Bay Area waters through filtration and boosting the overall health of the surrounding ecosystem in the process.

American Oystercatcher illustration by Lia Keener

Digging into the history of the East Bay and uncovering the events which have created the ecosystems and infrastructures now in place reveals the injustices built into modern day society. Taking action to protect sacred sites and restore critical native species to local waters are important steps that the Bay Area community is taking, because recognizing, understanding, and righting the wrongs of the past are essential for moving forward toward a better future.