Last updated April 2025.

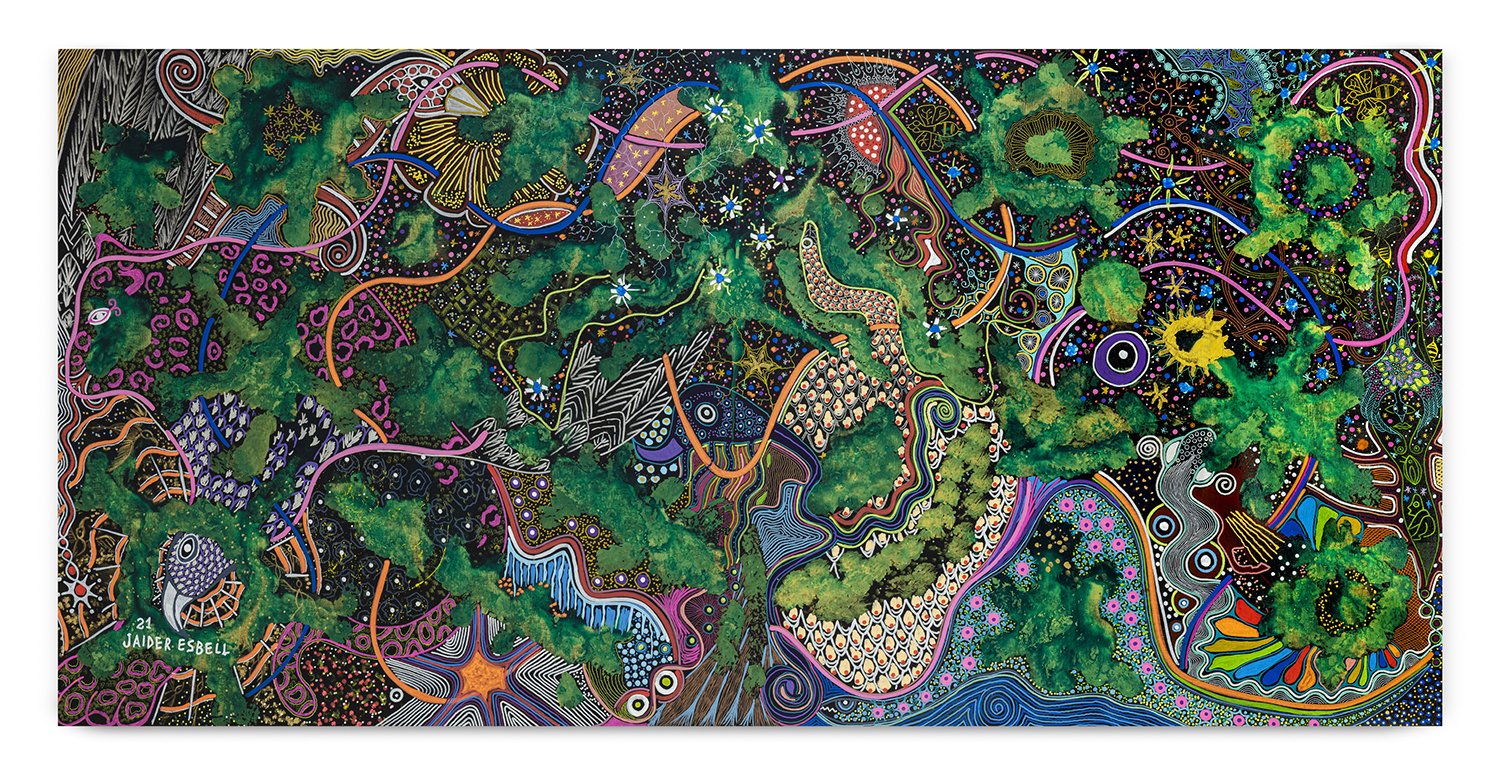

For anyone interested in the liberation of land, people, and more-than-human beings, it is incredibly meaningful to see creative work that critically engages with nature. Take Indigenous Brazilian artist Jaider Esbell’s piece The Conversation of Intergalactic Entities to Decide the Universal Future of Humanity (2021). It speaks to the nagging uncertainty that so many feel amidst the climate crisis and environmental destruction globally. The piece’s centerless forest canopy, gazing eyes, stars, and meandering bright and colorful lines remind viewers of the cosmic and existential nature of the current moment. Yet, through the representation of ancestral Indigenous cosmologies, the artist implies that our collective fate is in no way sealed. There is a possibility for transformation. As students, we are uniquely positioned to shape such a transformation. Coming from a generation that is experiencing rising levels of eco-anxiety due to inadequate action by governments globally and an awareness of late-stage capitalism, we are hungry for strategies towards change and ways to make sense of our world—so why not look to art?

Creatives have always influenced perspectives on nature, revealing a deep, albeit complicated, relationship between artistic mediums and environmental narratives. The writings and works of romantics such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau reflect some of the earliest sentiments of mainstream American environmentalism. Their work, however, emphasized a Pristine Myth of Nature that sparked interest in preservation and National Parks, both of which were used to displace Indigenous communities and restricted access to nature through racist policies. However, other traditions of art, particularly those forged by people of color, queer people, disabled people, and other subaltern people in society have proven that art can resist these systems of oppression. Particularly, “artivism”—a hybrid between art and activism— has strong potential to push the environmental movement forward. And further, this practice of blurring the lines between art and environmental activism is something our campus and flourishing student environmental community can and should play a role in furthering.

A good starting place is to understand where artivism comes from. The term has been linked back to the Chicanx muralists of East Los Angeles, as well as the Zapatistas of Chiapas, Mexico. Both have used art and aesthetics to expand community consciousness around justice and identity. Chicanxs placed their focus on Mexican-American culture and systemic injustice against Latine communities from the 1960s to 1980s while the Zapatistas painted about Indigenous autonomy and fighting neoliberalism in Mexico. Both became well-known for making connections to global and transnational issues, as well as creating art communally. Thinking about media, posters and prints have long been visual forms of resistance, whether posted around public spaces or used during protests and direct actions for multitudes of causes (a beautiful archive has been kept of Palestine posters since 1900). Art forms like zines are also historically radical, rooted in underground publishing, highly specific local subcultures, and social issues. Even our campus has a legacy of creative student activism to be honored, from the Free Speech movement to the artists of the Third World Liberation Front that helped win the Ethnic Studies Department. And of course, artists long ago began connecting the dots more specifically between art, activism, and the environment. El Teatro Campesino is a theater company that was born on the sidelines of the 1960s California farmworker movement. Translating to “the farmworker’s theater”, they began as a community-based group, using performances and skits to galvanize everyday people to boycott grapes and bring to light the sociopolitical realities of life in the agricultural fields of California. Musically, Black Americans have historically used the Blues, Hip Hop, and soul music to speak on environmental racism and injustice. All of these forms of creative expression through artivism are also forms of radical imagination.

Today, this practice of environmental artivism is alive and growing, from art builds at mass climate mobilizations to even the mainstream art world, where artivists like Jaider Esbell and Emerson Pontes (who blends performance and drag-like embodiments in the forests of the Amazon) have broken onto the scene. Though some still suggest a clear binary between art and activism, we look to politically engaged artists, writers, and poets (whether they identify as activists or not) who affirm that art is concerned with resistance and repair. Art is what Olivia Laing, author of Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency, calls a “training ground for possibility”. Such a beacon is just what we, as college students attuned to environmental issues, are inspired by as we graduate into a world facing climate catastrophe. If not at the university once ranked #1 in sustainability in the world, then where?

As climate and environmental activists, instead of throwing soup at famous art, we choose to make art ourselves. We know that beyond just “raising awareness”, the right art can teach us new ontologies or ways of being in relation to nature that resist extraction and domination. What’s more, eco-creativity is already being practiced by environmental groups here on campus, from activist art installations and zines to student journals publishing eco-art and writings. We empower students to get involved in existing and emerging eco-creative opportunities on campus or to dream up their own (which is what we’ve done here at The Leaflet). We also affirm that art isn’t only impactful in student-led spaces. There are already incredible examples of environmental classes being offered in art history and performance studies, as well as research connecting artists with ecology. We want to see such institutional opportunities expanded within the academy and with community involvement. We call on the College of Natural Resources, environmental studies courses, instructors, and our classmates to take art (not just scientific writing and the written word) seriously. Find ways to integrate examples of art in class and allow students the option to research, or better yet, create art for assignments. It will take all of us to bolster an eco-creative movement and creative interventions in the fight for our future.

Contributors: Alexandra Jade Garcia ‘24, Jacqueline Canchola-Martinez ‘25, Tiva Gandhi ‘27, Emily Martinez Robles ‘26, Ella Jaravata ‘26, Simone Garcia ‘26, Zora Uyeda-Hale ‘26