MIT released an article in late October that showcases a newly-discovered carbon capture prototype that can draw CO2 directly from the air more efficiently than any other technology currently available.

This comes less than a year after the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a special report on the progress that’s been made to keep warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius. The results were disheartening and suggested that only implementation of carbon-negative technologies could keep us below this goal.

The MIT prototype is part of a suite of such carbon-negative technologies that collectively are called Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR). While CDR could be a necessary tool to slow climate change, relying on it could also be a dangerous stalling tactic that diverts efforts to reduce fossil fuel consumption. As more carbon capture technologies come online, it is important to determine how much we can safely rely on them in the fight against climate change.

The first carbon capture plant, run by Climeworks, opened in Switzerland in 2017. (Source: Dezeen.com)

The prototype could be a revolution for CDR. Its footprint and energy requirements are much smaller than other similar technologies. These have been big constraints for companies like Climeworks and Global Thermostat.

Climeworks has a product pictured above that can capture CO2 from the surrounding air, but it’s fairly energy-intensive and inefficient for its size. The model removes 2.46 metric tons of CO2 per day in ideal conditions. While this may seem like a lot, total yearly emissions reach about 37 billion tons of CO2, about half of which (17 billion tons) ends up in the atmosphere. The company’s website estimates that 15,800 KM2 would be required to cover yearly pollution needs. And with a current cost of 500-600 dollars per metric ton (which could go down as scale increases), it’s not the most economically feasible.

Global Thermostat’s technology removes CO2 directly from the power plants’ flues. This is useful because it can run off the excess heat the plants generate. However, because it cannot pull CO2 directly from the ambient air, GT doesn’t combat emissions from transportation, which is a massive contributor to pollution.

The MIT prototype is less expensive than either model, has a much smaller footprint, and requires less energy. It can be either freestanding or attached as a scrubber to power plants. However, the freestanding model has only been tested with CO2 concentrations greater than 5000 parts per million, which is over 10 times the current atmospheric level of about 400 ppm.

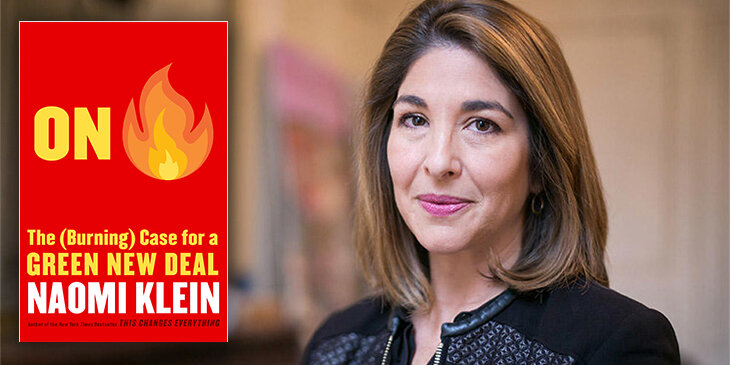

These concerns over CDR’s efficacy are nothing new. Noted climate scholars Naomi Klein and Amitav Ghosh feel that IPCC’s faith in these technologies is nothing short of religious. They compare society’s trust in climate-saving technology to be akin to believing the Messiah will save our society in the future.

Klein in particular worries that CDR could just be a stalling tactic for those who don’t want to deal with the challenge of moving to renewable fuels. She highlights the 25 million dollar prize that Virgin Airlines CEO Richard Branson is offering to the first person who can find a technology to sequester one billion tons of carbon per year. Klein sees this not as a beneficent investment in a valuable climate technology, but a shrewd business move. She argues that Branson is purposefully putting the brunt of climate efforts onto the sequestration route because it frees his airline from action--if someone discovers such a technology, he wouldn’t need to worry about the massive amount of carbon his jets pump into the air each year.

Naomi Klein has just released her second book on climate change, titled “On Fire”. (Source: Town Hall Seattle)

In many ways, this makes sense. CDR technology is still nascent, and under scrutiny its promises can seem far-fetched, which is why Naomi Klein sees it as more of an advertising gesture than a real solution. Plus, the more we focus efforts on climate-negative technology, the less we focus on slowing the use of fossil fuels, which is the root of the problem.

There is also substantial economic data that other climate actions have far higher benefit-cost ratios, which include carbon sequestration tactics such as landscape restoration that provide other benefits to agriculture and water systems.

The IPCC data is clear. Unless extreme measures are taken in the next twenty or thirty years to cut emissions, we will need carbon-negative solutions to stay below the 1.5-degree threshold. Direct carbon capture is promising, because if it works as intended--which is a big if--it could lock that carbon away in rocks for millennia. But that doesn’t mean that it should work alone. There are a myriad of other projects that can help pull carbon from the air, and, most importantly, reduce society’s consumption of fossil fuels.